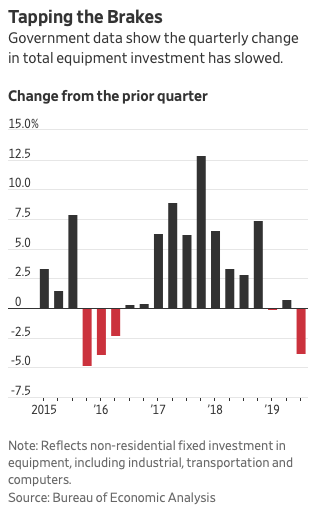

Many of the biggest U.S. companies are moderating their spending on equipment and other capital investment, as an uncertain business environment prompts some to postpone or shelve otherwise promising projects. That could pose a continuing drag on economic growth.

The pullback began as trade tensions escalated last fall, leaving companies unsure about their supply chains, pricing and profits. It has continued amid signs of slowing global growth and increasing consumer concerns about the future. Household names like Harley-Davidson Inc., AT&T Inc. and Target Corp. are joining small businesses in putting the brakes on investment.

Some companies have warned it could continue into next year, when the presidential and congressional election is expected to add even more uncertainty to business decision-making.

Companies slow capital investment for a variety of reasons, and few have explicitly tied their cutbacks to trade, typically citing slowing demand or project delays instead. Still, economists and analysts point to timing: The pullback began in third-quarter 2018, just as the U.S. and China began threatening and then imposing significant tariffs on one another’s goods.

Moreover, surveys of business sentiment show that trade tension has weighed on spending plans; earlier this month, the Atlanta Federal Reserve found that 12% of surveyed businesses—including one in five manufacturers —cut or delayed capital spending in the first half of 2019 because of trade tension and tariff worries, double the rate in the first half of 2018.

“The trade uncertainty has been a major drag on U.S. investment,” Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom said. Mr. Bloom partners with Steven Davis of the University of Chicago and the Atlanta Fed on a monthly survey of business uncertainty.

They estimated that $40 billion in investment was lost in the first half of 2019 from trade issues, amounting to a reduction of about 3% based on $1.4 trillion in estimated nonresidential fixed investment, or capital spending on equipment, buildings, vehicles, computers and the like. Since 2000, such investment has grown at 4% a year.

“Some of this will come back—projects delayed—but some of this will be permanently lost,” Mr. Bloom said. “Factories that never open, IT projects that get shelved or R&D projects that are passed over. So I think there is a real long-run cost to U.S. growth.”