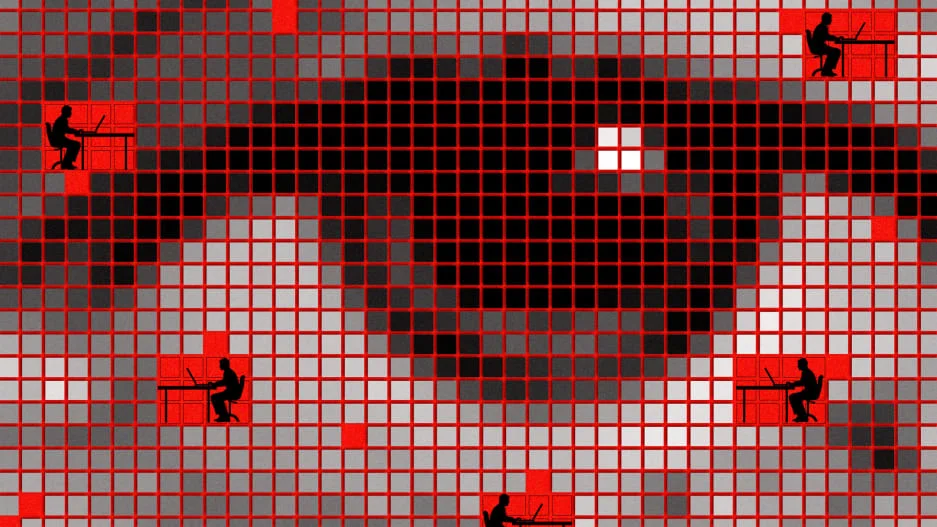

Considering all the ways that companies are using technology to keep tabs on their employees, it makes perfect sense that some believe Big Business is fast becoming—and, indeed, may already have become—Big Brother.

Last year, the research firm Gartner found that more than 50% of the 239 large corporations it surveyed are using “nontraditional” monitoring techniques, including scrutinizing who is meeting with whom; analyzing the text of emails and social-media messages; scouring automated telephone transcripts; gleaning genetic data; and taking other such steps. That’s up from just 30% in 2015. And Gartner expects those ranks to reach 80% by next year.

“Technological advancements in several fields—big data analytics, communications capture, mobile device design, DNA testing, and biometrics—have dramatically expanded capacities for worker surveillance both on and off the job,” Cornell’s Ifeoma Ajunwa and New York University’s Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz warn in a 2016 law review article.

“The American worker,” they add, “must now contend with an all-seeing Argus Panoptes . . . that allows for the trawling of employee data from the Internet and the employer collection of productivity data and health data.”

Yet as scary as all of this sounds, invoking a figure from Greek mythology—Argus Panoptes was a hundred-eyed giant ultimately slain by Hermes—is actually quite apt. That’s because, while the specter of employers widely abusing workers’ privacy looms large, it doesn’t seem to be much of a real issue in most offices, factories, and shops across the country.

“Concern is very broad but not very deep,” says Lewis Maltby, the president of the National Workrights Institute and a longtime advocate for protecting the civil liberties of employees.

When he hears from workers, he notes, it’s typically not because management is poking around into private matters; it’s because their personal information was erased without any warning when they left their job and their employer reclaimed a company-owned cellphone. “That’s the most common complaint,” Maltby says.

One possible explanation for such apathy, Maltby suggests, is that many workers may not comprehend the full extent to which their employer is probing into their activities. And those that are aware may well realize that, generally speaking, there are stark limits to how much they can push back legally.

“If the employer has a reasonable purpose for the monitoring program, it’s over,” Maltby says. “The camera in the women’s bathroom doesn’t make it. But if a company reads employees’ email because it’s concerned about sexual harassment, they can argue there’s a legitimate purpose. It passes the test.”

Ajunwa, Crawford, and Schultz cite another factor, too: Whereas employers were once heavy-handed in their tactics—think of the way General Motors hired Pinkertons in the 1930s to conduct an espionage campaign against labor activists—they’ve now persuaded employees that sharing personal information is in their own interest.