WS Development's corporate headquarters in Chestnut Hill, Mass., and designed by Elkus Manfredi Architects Photo: Jasper Sanidad.

The potential of lighting to improve occupant health and well-being is increasingly attracting the attention of project owners and end users. In commercial environments, good design has become synonymous with talent hiring and retention. The benefits of well-lit spaces map across other regularly occupied building typologies, such as residences and schools, as well as patient rooms in healthcare and assisted-living facilities.

“If you don’t get the lighting right, it’s not going to be an environment anyone wants to spend time in,” says Elizabeth O. Lowrey, principal and director of interior architecture at Elkus Manfredi Architects, in Boston. “It all goes back to making people feel good and look good.”

“Clients are increasingly requesting and expecting lighting systems and applications that can support human health and well-being and make an impact on the circadian system,” concurs Mariana Figueiro, director of the Lighting Research Center (LRC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, in Troy, N.Y., where she is also a professor at its School of Architecture.

In response to demand, lighting manufacturers are launching new products that they allege to be attuned to our circadian rhythm. Yet the skeptical architect and end user have to wonder: How much of this is marketing versus actual science? Is circadian-attuned lighting any better than conventional products?

What You Can’t See

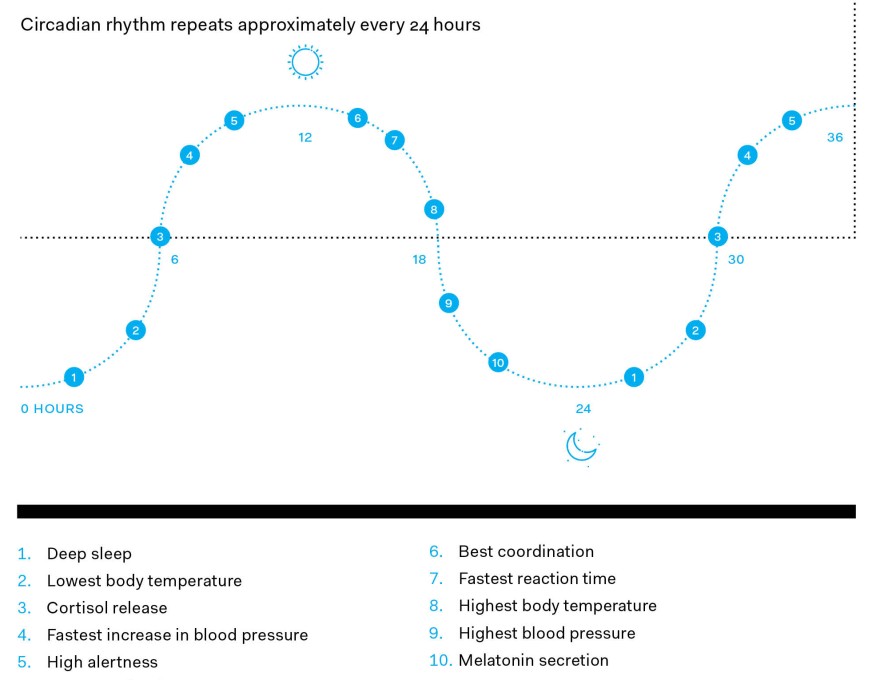

Both daylight, courtesy of Earth’s 24-hour light–dark cycle, and electric light can drive our circadian system, our internal clocks that regulate daily behaviors and the timing of biological processes, such as the release of the hormones melatonin and cortisol, which help control our blood sugar and affect our energy levels.

Several characteristics of lighting, including quantity, spectrum, timing, duration, and distribution, determine its nonvisual effects on our bodies and minds. The influence can be positive, but also negative if, for example, light is delivered at the wrong time. Think screen time on electronic devices before bed or in the middle of the night. The disruption of circadian rhythms has been associated with health problems such as metabolic diseases, depression, and some types of cancer.

“We don’t fully understand everything there is to know about light’s nonvisual effects, but we know enough from the research over the past 30 years to be able to apply light to improve sleep, mood, and well-being in a variety of environments,” Figueiro says.

The LRC, for one, develops metrics and tools to help lighting designers understand and apply circadian light in the built environment. Circadian stimulus (CS) measures the effectiveness of the retinal light stimulus for the human circadian system from threshold to saturation; in other words, this metric allows designers to compare the ability of different light sources to stimulate the circadian system. With funding from the U.S. General Services Administration, the LRC has conducted several studies that found office workers receiving high CS throughout the workday felt more energetic and alert than workers receiving low CS. The former group also experienced better sleep and felt less depressed.

Daylight, Mimicked

Generally speaking, natural is best and lighting is no exception: Daylight is the ideal source for regulating the circadian system. However, people tend to spend most of their day in interior environments, the majority of which Figueiro believes are under-lit: “Due to restrictive energy codes, daytime light levels in buildings are often too low or at threshold for activating the circadian system,” she says. “Even in open offices with many, large windows, workers do not receive enough daylight to stimulate their circadian system, due to factors such as season, cloud cover, desk orientation, and window shade position.”

Supplemental electric lighting is thus a necessity, and recent technologies have enabled and improved the ability of fixtures to work in tandem with daylight. For example, luminaires with integrated photosensors and automatic dimming can maintain consistent light levels regardless of fluctuations in available daylight. Advancements in LED technology have also fostered the creation of tunable white light systems, which mimic daylight patterns by adjusting correlated color temperature (CCT) and brightness levels throughout the day.