A company survey in July found that nearly 70 percent of Twitter employees wanted to continue working from home at least three days a week.

From his home base on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, Anton Andryeyev is running Twitter’s efforts to chase Russian bots and other rogue actors off the platform. A year ago, he traded his office in the company’s San Francisco headquarters for this tropical home office two thousand miles away, surrounded by standup paddle boards and a monitor large enough to see his entire 25-person engineering team all at once.

Andryeyev’s remote office represents a sweeping experiment in the future of work: allowing white-collar workers to work from anywhere, forever.

Corporate America has long been defined by physical offices. But in a few short weeks, the pandemic upended that as thousands of companies mandated their employees work from home. What many thought would be a temporary workaround is now a mass experiment with no end in sight, as many companies await a vaccine or other developments to ensure workers’ safety.

While many companies are anxious about the new reality, fearful of reopening and worried about the loss of workplace connection, some employers have embraced it — even going so far as making remote work permanent. Outdoor apparel company REI, Facebook and Ottawa-based Shopify have all announced some measures making work from home the new norm.

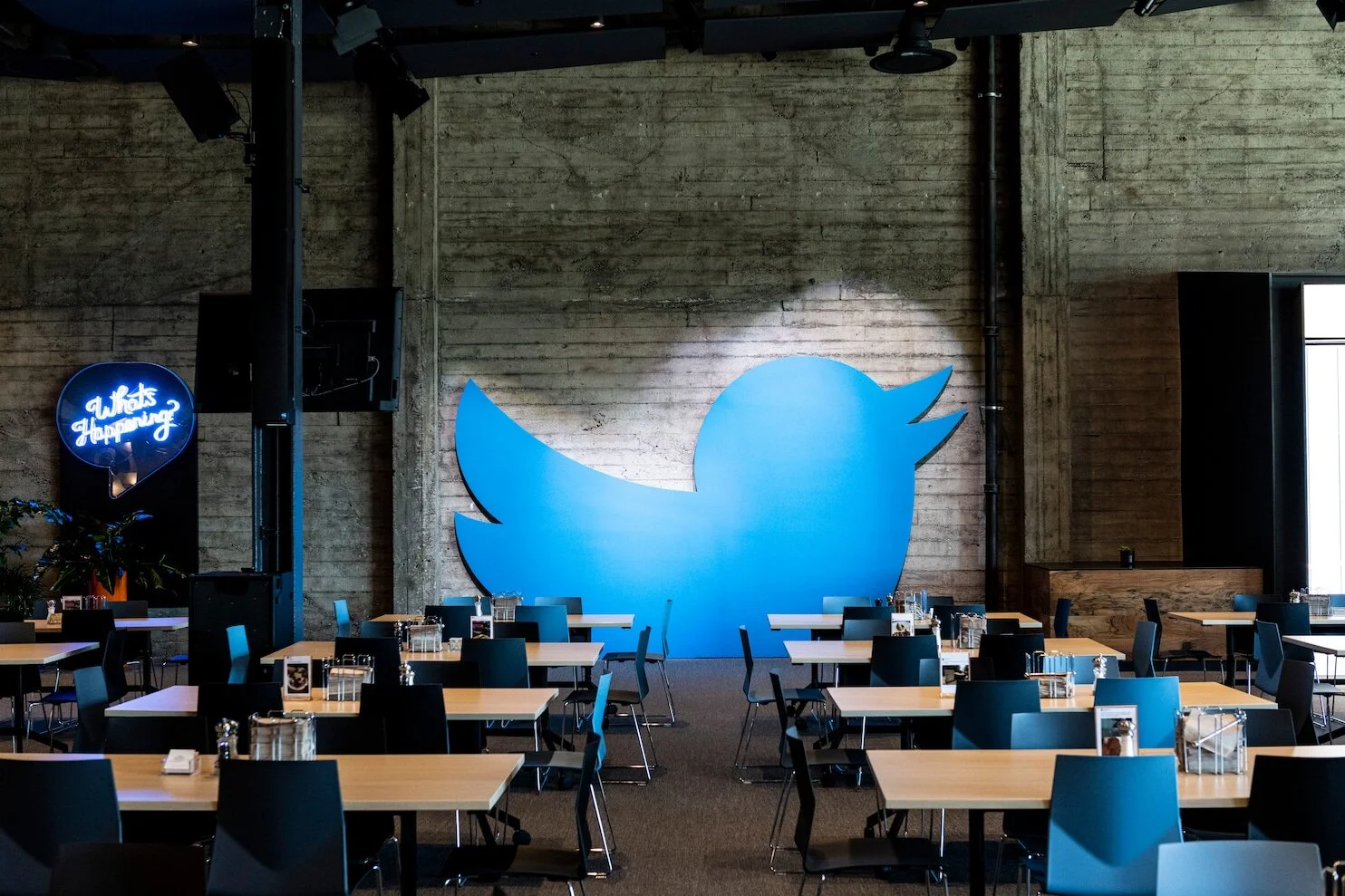

Twitter, the first major U.S. company to make a public announcement in May about its permanent work-from-home plans, has a big head start in identifying the pitfalls and advantages of work from home.

For the last two years, Twitter has been quietly dismantling its office culture, making changes that resulted in blessing employees like Andryeyev who asked to relocate — whether it was Hawaii, rural Ireland or back home in a cheaper state. However complicated, the official policy on employee relocation requests was “get to yes.” The effort began with an off-the-cuff email in 2018 by chief executive Jack Dorsey in which he encouraged employees to work from home after a productive day doing so himself.

Twitter has been experimenting with building ways to better support Dorsey’s vision ever since, sending people in the same building to different rooms to test out virtual meetings, creating sign language systems and other rules for video conference etiquette, and preparing for a future when the company anticipates half of its employees will permanently work from home. (Prior to the pandemic, it was only 3 percent.)

“We’ve already been on this path, and the crisis just catapulted us into a future state,” said Twitter human resources chief Jennifer Christie, who said she believes flexibility for workers is the “fourth industrial revolution" because it will fundamentally change the way people work. “The future of work is offering employees more optionality.”

Twitter’s decision to allow its 5,200 primarily San Francisco-based employees to decide where they want to work has major implications for everything from its real estate and salaries to workplace culture writ large. The company could potentially usher in a new model for attracting and retaining talent based on worker-centric values of flexibility, autonomy and satisfaction.

Just this month, the company said it was subleasing three floors of its art deco office building in San Francisco. (The company says it plans to keep all its real estate worldwide and two of the three floors were already subleased.)

But the decisions led by Twitter and followed by other companies could just as soon herald the end of an era when great ideas at work were born out of daily in-person interactions — a hallmark of Silicon Valley thinking. Apple founder Steve Jobs described it as the creativity that comes from serendipitous run-ins with colleagues, telling his biographer that “creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions.” The ideas for Facebook and Google were generated in a college dorm room and a garage near Stanford University, while Dorsey has said he came up with the idea for the short-form micro-blogging service while hanging out with his co-founders in San Francisco’s South Park.

The result could be less innovative, more checked-out workers and empty tech hubs free of lunch-hour buzz.

Just six months after the coronavirus outbreak led thousands of companies to mandate that their employees work from home, 35 percent of the full-time U.S. labor force is still working remotely, compared to 2 percent prior to the pandemic, according to an August survey of 2,500 professionals by Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford University economics professor who specializes in distributed employment.

While accelerated by the pandemic, Twitter executives in exclusive interviews explained that the company’s shift to distributed work is ultimately about creating a model that gives employees more autonomy and freedom, which they believe improves morale, retention and productivity. The policy, which is now one of four official company goals, also gives Twitter greater ability to hire diverse and more affordable employees from all parts of the country.

“Our concentration in San Francisco isn’t serving us anymore,” Dorsey told investors in February.

The company has had its share of challenges. Some Twitter employees are struggling with scheduling across time zones, and executives had to formally cut down on video meetings, which spiked as people went home during the pandemic, to avoid Zoom fatigue, executives and employees said in interviews. They had to rethink their performance review system so it wouldn’t be biased against remote workers when people return to the office. Others said it was harder for employees to log on remotely during a recent major hack of the company’s systems, in which high-profile accounts like former president Barack Obama’s were taken over.

The biggest challenge, Mike Montano, the company’s vice president for engineering, said, is “the need to create space for social connection” that isn’t forced. Montano has been tweeting photos of his home office in San Francisco in hopes of inspiring others. He said you want to recreate “a water cooler effect,” a serendipity that lets people build connections that “aren’t transactional.”

He plans to stay largely remote after the pandemic, coming into the office occasionally and spending longer stretches of time with family outside California.