How would America’s greatest architect design a home office? Could Frank Lloyd Wright, who had visionary solutions for contemporary living—from sustainable design, air conditioning, even open-plan offices—have an answer to the search for ideal Covid-era remote working configurations?

A clue lies in the meticulously-restored Martin House in Buffalo, New York. Commissioned by workaholic businessman Darwin Martin in 1902, Wright considered it among his greatest achievements, on par with Falling Water in Philadelphia and the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Scholars consider cite the Martin House as a prime example of Wright’s prairie house style—a building characterized by broad, flat structures, and a free-flowing interior layout.

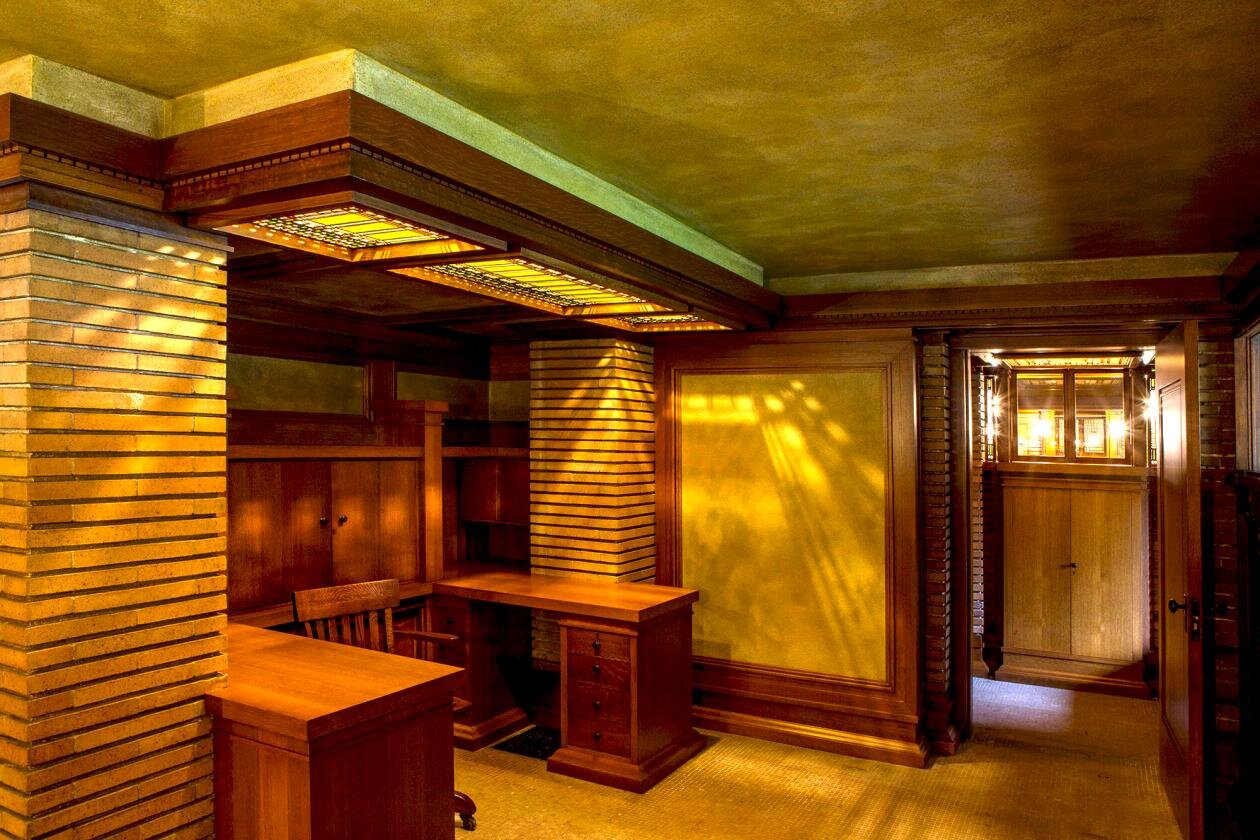

Wright designed over 500 homes over the span of 70 years, but the jewel of Buffalo’s Parkside neighborhood is one of the few with a dedicated work space. The Martin House’s 12 ft by 15 ft bursar’s office, as it was called, was designed to accommodate the owner’s compulsive work habits.

Darwin Denice Martin aka “the Bill Gates of his time”

As corporate secretary of the Larkin Soap Company, Martin was in charge of the bookkeeping of the thriving business. He worked 14- to 16 hour shifts, six days a week, and was known to carry lunch and an evening meal with him. “Martin began at the Larkin company at age 14 and worked so hard he was discovered asleep on the accounts books one morning having been there all night. I’d say, yes, he was a workaholic,” says historian Jack Quinan a leading scholar on Wright and curator emeritus of the Martin House Restoration Corporation.

Mary Roberts, Martin House’s executive director describes how the one-line entries in Martin’s diary revealed his stress. “Too busy to think; Busy all the time; Not a minute to despair; My blood is all out of order’.”

Apart from his all-consuming job at Larkin, Martin had investments in Toronto, Buffalo, and the western US, which meant more administrative paperwork. The custom-designed bursar’s office was a space where Martin could focus and to attend to those matters at home without distraction.

Wright introduced several solutions: First, he created a dedicated and discreet entrance to Martin’s man cave, concealing the door behind a low brick wall from the outside and behind a small door from the living room.

This was an upgrade from the layout of most home offices during this time. As Elizabeth Patton explains in her book, Easy Living: The Rise of the Home Office, the “chamber,” as they were then referred to, was typically located close to the main door so the man of the house can receive business associates without disturbing the rest of the home.

Wright’s signature art glass windows were smaller and positioned above the 4.5 ft bookshelves so Martin won’t be distracted by street traffic when he was seated. (He was 5 ft 6). He also included a stained glass skylight to infuse some light in the room.