Have you seen a car ad on television that shows the noisy chaos of the world outside the car before it pans to the driver inside the quiet, luxurious interior of said car, protected from the elements outside? The message you’re supposed to take from this juxtaposition is that this car is “tight”—sealed off from the world outside and all its perils.

This sealing up is done for a few reasons: it provides a quiet interior, for sure, and it makes your air-conditioning and heating more efficient because the car is less “leaky.” But it also comes with an unexpected side effect: the pollutants inside the car have nowhere to go, leading to a buildup of potentially toxic pollutants emitted from materials inside the car, and a buildup of carbon dioxide emitted from the car’s occupants. We regularly see levels of CO2 inside cars that are as much as four to five times higher than what we allow in buildings. Ever get sleepy while on a long drive with the family or friends? The high carbon dioxide levels in your car are contributing to that—it’s one of the reasons you’ve likely heard the recommendation to roll down your windows if you feel sleepy while driving.

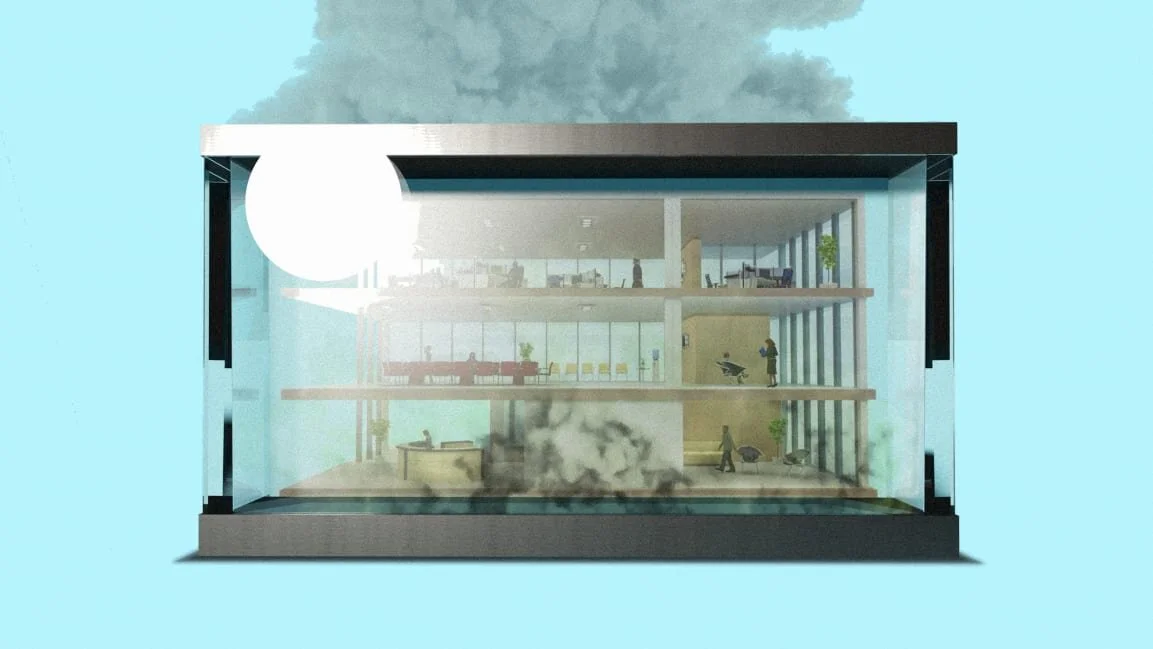

Buildings are the same. Like humans, they need to breathe. But, as with cars, we’ve done one hell of a job over the past 40 years of cutting off their air supply.

For over a hundred years, there have been efforts to figure out the proper amount of fresh air that needs to be brought into a building. Beginning around the time of the energy crisis in the late 1970s, we did our best to tighten our building envelopes and reduce ventilation rates in an effort to conserve energy. The goal for our homes and offices and schools was to make them less leaky.

We were very successful in these efforts. Kudos to the energy engineer pioneers in the 1970s for helping to alleviate the energy crisis in buildings. But maybe they should’ve consulted some health scientists along the way. The result of sealing up our buildings, as you likely guessed from the car story: a buildup of pollutants indoors. And with it, the birth of a phenomenon known as Sick Building Syndrome. So there you have it—if you don’t feel well in a building, you can thank a set of energy engineers who decided that the best way to tackle the energy crisis was to choke off your air supply.

Studies have found that in North America and Europe, we spend 90% of our time indoors. Some jobs have you out and about more, and kids tend to spend a little more time outside than adults—but for most of the developed world, it’s more accurate than you might think. (In some places and in some seasons, that 90% is actually an underestimate; in the United Arab Emirates, it can be more like 99.9% indoors for some people.)

To put this 90% figure in perspective, it’s useful to think of what it means in terms of our own lives. By the time we hit 40, most of us have spent 36 years indoors. Try it for yourself: take your age and multiply it by 0.9. That’s your indoor age. If we are lucky enough to live to 80, most of us will have spent 72 years inside! When we look at it this way, in terms of years, it becomes obvious and intuitive that our indoor environment would have a disproportionate impact on our health.

Sometimes we think that all we really need to do to advance the Healthy Buildings movement is mention this 90% fact. After hearing that, how could anyone conclude that the indoor environment does not impact our health? Heck, we spend a third of our lifetimes in one little box on this planet—our bedrooms!

Here’s a weird but helpful way to think about all of this indoor time, courtesy of Rich Corsi, dean of engineering and computer science at Portland State University: “Americans spend more time inside buildings than some whale species spend underwater.”

What?! It’s kind of hard to wrap your head around this—that whales spend more time on the surface than we, as land mammals, spend outdoors—but it’s true. We would never go about trying to understand whales by studying the air they breathe when they are at the surface; we study them where they live, underwater.