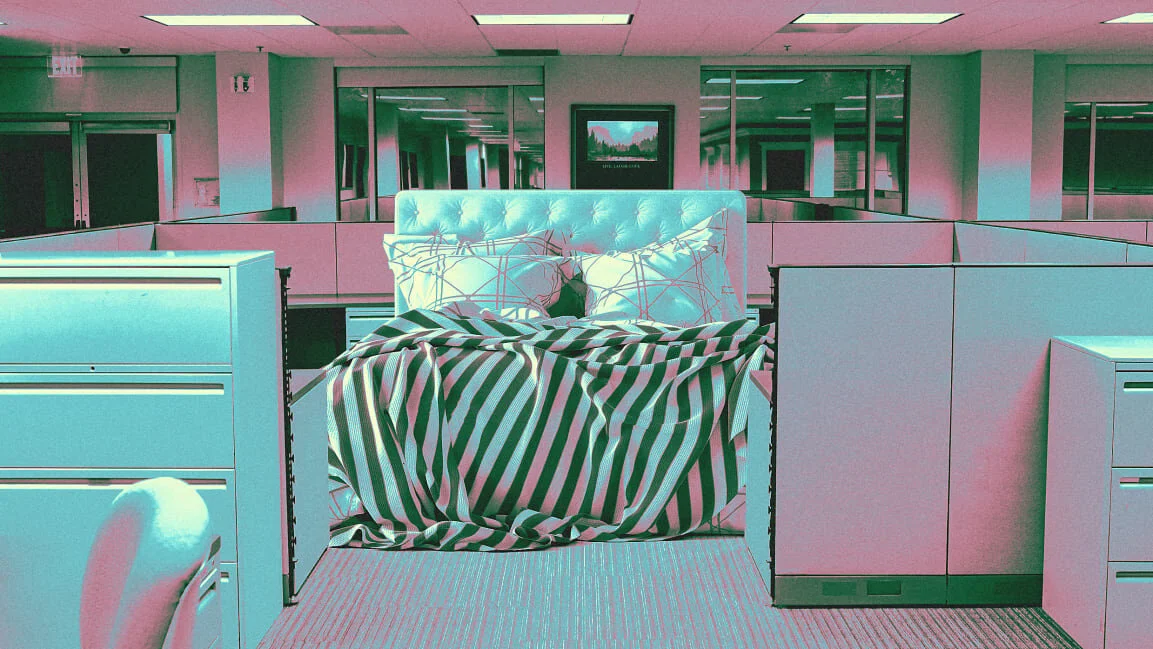

World leaders are looking at vacated office buildings and shuttered retail shops and seeing one thing: housing.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused many commercial spaces to empty out, either as a precaution for the safety of workers or as the result of going out of business. Top officials are hoping these spaces can be adaptively reused.

In the U.S., Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson says that as people abandon offices to work from home, the vacant space could be adapted to address housing shortages. “That’s going to free up a lot of commercial space, which can be converted to affordable housing to take some of the pressure off,” he told Fox Business in late June. “Virtually all of the major cities have significant spaces that can be used, and we’re encouraging [city officials] in their planning now . . . to begin to take this into consideration.”

A week later, U.K. prime minister Boris Johnson stood at a podium decorated with the words “Build Build Build” to announce “Project Speed.” This plan, expected to come into force in September, would accelerate infrastructure projects and push through home building and conversion projects by reforming the planning and zoning process. Blaming “newt-counting delays in our system” for the slow pace of home building in the U.K., Johnson’s plan would allow most commercial spaces to convert to residential uses without a planning application.

These kinds of conversions are easier said than done, says Sheila Botting, president for the Americas at the commercial real estate company Avison Young. The office buildings Carson has in mind are not great candidates for residential spaces. “They’ve got giant floor plates,” she says, meaning most of the subdivided spaces would be windowless caves. “And to go from the windows back into the core is very deep and therefore very tricky to make a conversion to residential.” She says it can be done, but only about 10% to 20% of office buildings have a small enough footprint and plumbing in the right places that they can feasibly be turned into housing. “Most of them, because of the density, because of the math and financial feasibility, it does make sense to level it to the ground and start over again with a specific design.”

Beyond physical limitations, there are also zoning challenges to deal with, according to Danielle Lewinski, vice president and director of Michigan initiatives for the Center for Community Progress, a nonprofit focused on vacant property in cities.

“The underlying zoning of some of these spaces is quite antiquated,” she says. By only allowing a single type of use—such as office space or retail—the zoning automatically precludes conversion to housing, or to mixed-use development that can meet a wider set of needs. In many municipalities, the office buildings Carson wants to convert to housing are only zoned to be office buildings—subject to rules that are set at the local level and which often require a lengthy public process to change.